We propose the gradual phasing out of the medical marijuana system in favor of one class of marijuana.

One of the primary myths associated with marijuana is, unlike other higher-risk drugs, marijuana is non-habit forming, or not addictive. This is one of the more dangerous and pervasive myths regarding marijuana. In reality, marijuana users are at risk of developing cannabis use disorder (CUD), formerly referred to as abuse, dependence, or addiction.

CUD is characterized by difficulty controlling intake, development of tolerance, and withdrawal within a period of 12 months. Persons with CUD may suffer from problems at school or work, give up activities they previously enjoyed, or withdraw from their social network (Patel and Marwaha 2022).

CUD is clearly a concern and refutes the broad conventional wisdom about marijuana not being addictive. And, of course, with addictive properties comes the potential for significant withdrawal symptoms. Before the 1990s, many doubted that quitting marijuana after periods of heavy use could lead to similar symptoms of withdrawal seen in other illicit drugs. However, as marijuana use began to rise over the next two decades, more patients began to seek treatment for marijuana-related disorders, including dependence, cognitive deficits, and psychosis.

Researchers began to see that discontinuation of regular weed use was frequently associated with behavioral, emotional, and physical symptoms that disrupted daily living and were associated with relapse (Bonnet and Preuss 2017).

Based on support from neurobiological, clinical, and epidemiological studies, cannabis withdrawal syndrome (CWS) was added to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) in its 2013 edition (Livne, et al. 2019). In persons with CWS, quitting weed causes mood and behavioral symptoms like irritability, nervousness/anxiety, sleep difficulty, decreased appetite or weight loss, depressed mood, and agitation.

Individuals can also suffer from physical discomfort and complain of headaches, night sweats, abdominal pain, tremors, dizziness, and fatigue (Bonnet and Preuss 2017). In a study of 1,527 marijuana users, the most common side effects experienced post-cessation were nervousness/anxiety (76.3%), hostility (71.9%), sleep difficulty (68.2%), and depressed mood (58.9%) (Livne, et al. 2019).

Generally, symptoms of weed withdrawal begin within the first 24 hours of abstinence, peak by day three and can last for up to two to three weeks (Patel and Marwaha 2022; Bonnet and Preuss 2017).

The primary risk factors for weed withdrawal are thought to be intensity and recency of marijuana use (Bonnet and Preuss 2017). Severity of marijuana withdrawal increases with that of marijuana dependence (Livne, et al. 2019).

Importantly, the medical community has been slow to respond to this growth in CUD and CWS. The changing social and legal landscape surrounding marijuana use, coupled with the increasing potency of marijuana (Carliner, et al. 2017), leaves vulnerable populations at even greater risk to the potential harms of weed dependence and withdrawal.

Ruben Baler, Ph.D., an expert on the neuroscience of substance abuse and addiction, believes marijuana is medicine the same way opium is a medicine. Like marijuana, opium is a plant with active principles, which can be synthesized into drugs with real medical purposes after undergoing clinical trials. Dr. Baler believes marijuana should be treated the same way.

Like opium, marijuana has ingredients with medical potential but those ingredients are complex. Before prescribing them for specific medical applications, evidence-based conclusions must be determined through the traditional trial process. As Dr. Baler says, “we don’t deploy medications with that kind of complexity” without studying their potential impact. “That wouldn’t be a medicine, it would be ‘magic realism.’” According to Dr. Baler, the pendulum on medical marijuana has swung too far towards just acceptance based purely on anecdotes. That pendulum must swing back towards science and evidence. (Baler 2021).

Medical scientists have seen the public’s trust in them wane over the last several years. Many supporters of medical marijuana share a broader skepticism about doctors, scientists, and the scientific field. While some may think this a harmless side effect of the increased acceptance of marijuana as a potential treatment option, it could also have the effect of dissuading patients from seeing licensed doctors for medical consultation and instead going to medical marijuana companies for the same information. These two actors are not on the same level. One group recommends products and treatment options, which have been through rigorous scientific studies. The other pushes their own products as solutions to any number of medical problems but without clarity as to those products’ potential costs or benefits.

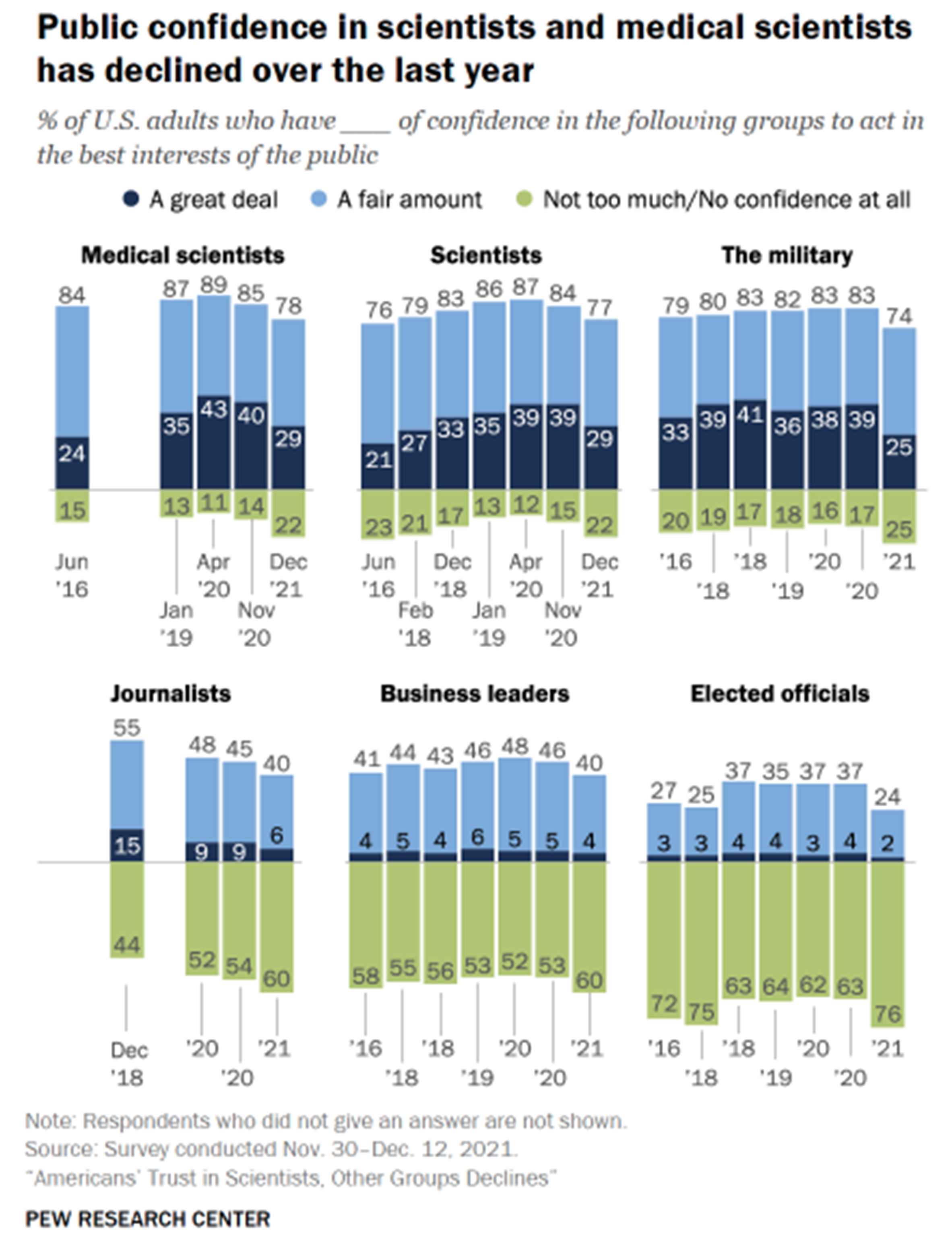

Aside from the obvious issues with medical marijuana companies filling the dearth of research into the costs and benefits of marijuana with their own heavily biased research, the fact that this type of pseudoscience is taking advantage of the public’s declining lack of trust in experts, which one can see in the figure below (Kennedy, Tyson and Funk 2022). The anti-vaccine movement, which began years ago but has culminated in the negative reaction to the development and delivery of the vaccines against COVID-19 is but one example of the public’s growing distrust of experts whose views and knowledge underpin much of the stability of the country’s key institutions.

The difference between the two groups could not be clearer, but for many patients, the line is blurred and both are viewed as two sides of the same coin.

For instance, some medical marijuana companies feature FAQ sections on their websites in which they direct patients to consult with the company to find a doctor who will recommend marijuana as a treatment if their normal doctor will not. In addition, dispensary staff are portrayed as experts who will guide patients in selecting correct products and dosages. This is a dangerous precedent, which legitimizes medical marijuana as a viable medicine when it does not deserve to be labeled as such.

Without a set of large-scale studies proving either that medical marijuana products are viable treatment options for various medical issues or options that have limited benefits and potentially serious side effects, the government and the medical community are at a disadvantage.

The medical marijuana industry is in a position to take advantage of this lack of research by pushing claims that may or not be true, but tap into public distrust of the medical community (often, ironically, because they are too focused on just making money) and the conventional wisdom that marijuana is safe for people across the board. It is this veneer of legitimacy that must be stamped out.

We propose the gradual phasing out of the medical marijuana system in favor of one class of marijuana.

Michael M. Michaud

Contributing Author, Public Policy

Public policy and communications professional with a focus on the intersection of public policy and business.

About Weedless.org

Weedless.org is a free, web-based resource and community created by a team of healthcare professionals and researchers. We distill the facts about marijuana use and its effects into practical guidance for interested persons or for those who are thinking about or struggling to quit weed. Finding reliable, easy to understand information about marijuana should never be a struggle—that is why our core mission is to provide the most up to date information about marijuana use, abuse, addiction, and withdrawal. While we seek to empower individuals to have control over their use, we are not “anti-weed” and we support efforts to legalize adult marijuana use and study.